The little-noticed end of a historic bond-market bailout by the Federal Reserve left fossil fuels stronger than before, highlighting Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s climate-hostile actions and the near-inevitability of future bailouts.

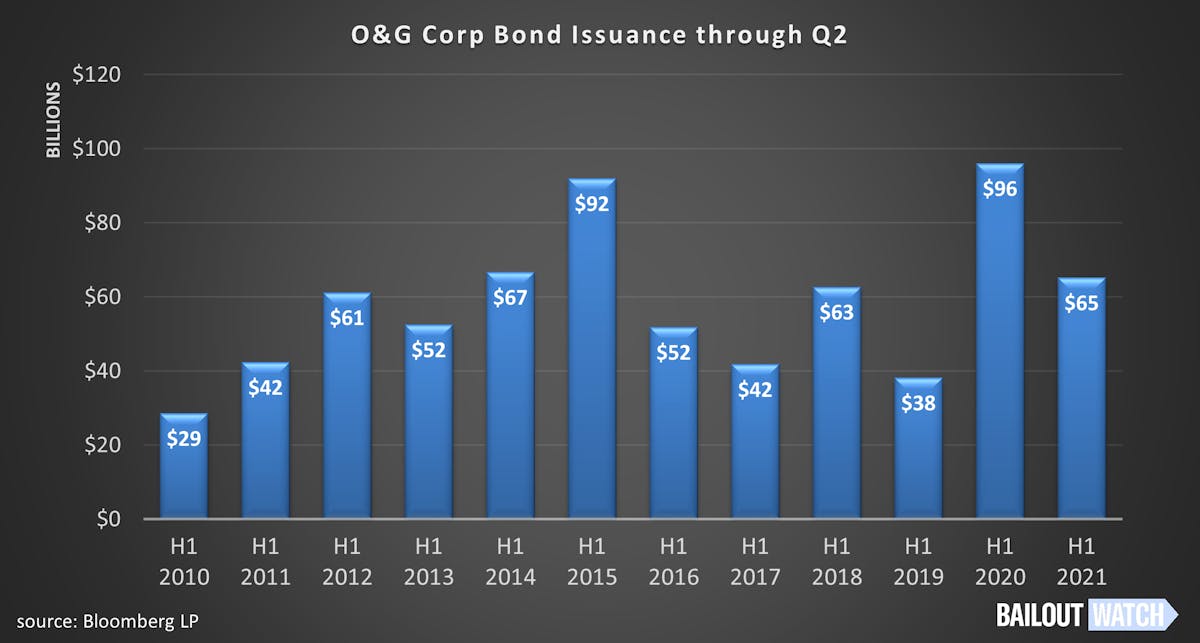

As the program wrapped up, its support of oil and gas was clear in the data, according to new BailoutWatch tallies: The industry was on track for its second-biggest year of bond issuance, with $76.4 billion in new bonds issued, after its biggest year in 2020. Since the program's inception, polluters have issued over $183 billion in corporate bonds. Oil and gas companies have already spent $53 billion on acquisitions this year.

The Federal Reserve announced earlier this month that it shuttered the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF), a program that propped up the fossil fuel industry by ensuring bond issuers’ continuous access to cheap debt. Despite calls from activists to use the pademic’s economic destruction to reduce fossil fuels’ power, the Fed overinvested in oil and gas, according to July 2020 analysis by InfluenceMap.

Part of the CARES Act stimulus law passed in March 2020, the SMCCF was the cornerstone of a suite of programs aimed at supporting the economy through pandemic shutdowns. It used an entity backed by taxpayer money to buy corporate bonds for the first time in the Fed’s history. By purchasing previously-issued bonds from private investors, the Fed was able to claim it did not favor any particular industry.

The SMCCF fueled a historic borrowing bender by oil and gas companies, which issued more than $100 billion in new debt by the end of 2020.

Meanwhile, the biggest oil and gas companies enjoyed $8.4 billion under a separate provision of the CARES Act. Smaller polluters benefited from changes to the Main Street Lending Program that allowed them to pay down bank debt with government-subsidized loans.

The shored-up fossil fuel industry continues to benefit from tens of billions in domestic and international subsidies. For stronger companies, bailouts and subsidies enabled a wave of acquisitions.

The SMCCF’s legacy will likely be addressed at a hearing Thursday by the House Financial Services Committee’s Subcommittee on National Security, International Development, and Monetary Policy.

The Fed launched the SMCCF on March 23, 2020 and stopped buying bonds in December. As of August 31, all bonds and exchange-traded funds held by the facility had matured or been sold.

The program’s end coincides roughly with the 13th anniversary of the collapse of investment bank Lehman Bros, which touched off the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. To address that crisis, the government responded with controversial bailouts worth hundreds of billions of dollars for banks and other struggling companies.

To make future bailouts less likely, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, an overhaul of financial regulation that gave the Treasury Department, Federal Reserve, and others increased power to monitor and address systemic risks — those that could filter through the broader financial system and cause another meltdown.

Climate change presents the greatest risk to the broader financial system, many advocates believe, but so far financial regulators have failed to exercise their powers to address the threat. Dodd-Frank created a Treasury-led committee to coordinate systemic oversight, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC). Janet Yellen, President Biden’s Treasury Secretary, is under scrutiny regarding an upcoming report aimed at implementing Biden’s executive order on climate-related financial risk.

Powell, meanwhile, has faced harsh criticism from climate activists concerned about his preservation of the fossil fuel status quo in the course of his pandemic response. With Biden weighing Powell’s renomination to the job, many have urged the administration to consider Lael Brainard, a competing candidate with a stronger track record on climate. Brainard consistently resisted softening banking regulation and advocated for more Wall Street oversight.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen chairs the council of regulators charged with implementing President Biden's executive order on climate-related financial risk

Credit: Joshua Roberts/ Reuters

Some of the most biting criticism came from Sheila Bair, a Republican and former Chair of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Noting Powell has led a rollback of rules to prevent financial crises, Bair called financial regulation “his real weakness.”

"There are very real financial risks the banking system is exposed to because of climate," Bair said, and failing to treat climate as a serious systemic risk “disregards a key lesson of the financial crisis.”

A September 2020 study by NYU’s Simon Gilchrist and colleagues shows how the SMCCF benefited fossil fuel companies in particular. Initially, the study found, the program achieved its goal by reducing credit spreads — but only on bonds deemed eligible for purchase by the Fed. Ineligible debt, including from companies recently downgraded by major ratings agencies, saw spreads increase by 340 basis points, reflecting investors fears.

A significant percentage of these ‘fallen angels’ were beleaguered fossil fuel firms suffering from competition from renewables and reduced fuel prices. On April 9th, the program was expanded to include these “fallen angels” in the Fed’s purchases. The expansion reversed about two-thirds of the spread increase, vastly increasing the attractiveness of oil and gas companies' debt.

Following the amendment to the program, energy bonds grew as a percentage of the facility’s portfolio each month until August, when it peaked at 9.46%. At year’s end, the Fed had amassed $5.2 billion in corporate bonds, of which over $474.5M (9%) were issued by fossil fuels.

The Fed’s outsized support of energy debt went beyond providing liquidity to outstanding bonds and led to the highest period of new debt issuance for oil and gas. Oil and gas companies issued over $107 billion in new debt from the programs launch through the end of 2020, for a year end total and annual record of $148 billion. The impact has persisted: Through September 15, 2021, fossil fuel companies included in the SMCCF have issued $183.6 billion in new bonds while spending at least $53 billion on acquisitions.

Sheila Bair, a Republican and respected financial regulator, criticized Powell's Fed for being weak on climate

The Fed received similar criticism for favoring oil and gas producers through its Main Street Lending Program. Shortly following the announcement of the MSLP on April 9th, 2020, the Trump Administration met with fossil fuel industry executives and lobbied for changes to the program's requirements and limitations. Some of the provisions they called to change were prohibitions on borrowers using loans for debt repayments, aiming to prevent failing companies from refinancing. A letter from the Independent Petroleum Association of American (IPAA), the industry's largest trade group, informed the Fed that these provisions would “prevent independent gas and oil producers from using these facilities.”

On April 21st, 2020, then President Trump tweeted that he has instructed the Energy Department and Treasury to make funds available for “these very important companies.” Energy Secretary Dan Brouillette and Treasury Secretary Mnuchin advocated for the changes that would allow participation from more medium sized companies, opening the way for many struggling oil and gas firms. By the end of April, fossil fuel companies had obtained the changes they advocated for; the Fed revised the program to provide larger loans and allow loan recipients to make any debt or interest payment “that is mandatory and due”.

The apparent manipulation of the Federal Reserve’s program by fossil fuels caught the attention of the Congressional Oversight Commission, set up to monitor implementation of the CARES Act. During an August 2020 hearing, commissioner Bharat Ramamurti questioned Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren on the unusual events that led to “changes lined up exactly with what members of the oil and gas industry had requested.”

President Biden’s Executive Order on Climate-Related Financial Risk directs financial regulators to assess the climate-related risks to the government and the financial system and to issue a report by November 20. The report is seen as a test of the Treasury Department’s seriousness about climate action and Powell’s regulatory chops.